Functional analysis of the gut microbiota

The resident microbiota emerges as a key modulator of health and disease. Due to the complex composition of this ecosystem, it has been quite challenging in the past to establish the molecular mechanisms explaining microbiota function. Clearly, the microbiota protects efficiently against Salmonella spp. infections, as it occupies the gut lumen and interferes with efficient pathogen growth in that niche (termed "colonization resistance"; see external pagevan der Waaij et al., 1971call_made and external pageStecher and Hardt, 2010call_made). In collaboration with the laboratories of Bärbel Stecher and Andrew Macpherson, we are developing defined mouse models (germ-free mice as well as animals colonized with a defined microbial community). These will enable the analysis of the mechanistic basis of colonization resistance.

This approach has already provided us with first insights:

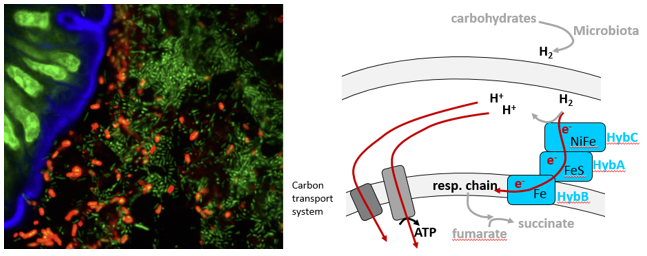

- S. Typhimurium utilizes microbiota-derived hydrogen to energize growth during the initial phase of gut colonization (Maier et al., 2013).

- Salmonella spp. subvert mucosal homeostasis and triggers inflammation to outcompete the resident microbiota (Stecher et al., 2007).

- Horizontal gene transfer between S. Typhimurium and strains of the microbiota can occur at unprecedented speed in the infected gut (Stecher et al., PNAS 2012; Stecher et al., Nature Rev. Microbiol., 2013; Diard et al., Science 2017; Moor et al., Nature 2017).

- At the end of an acute infection, the host mounts a protective immune response. This includes IgA antibodies directed against the O-sidechain of the S. Typhimurium LPS (Endt et al. 2010). These antibodies are secreted into the gut lumen and prevent further pathogen invasion (Endt et al. 2010; Moor et al. 2017; for details, see project by E. Slack). This promotes remission and re-growth of the normal microbiota. IgA and the re-growing microbiota cooperate in eliminating S. Typhimurium from the gut lumen of the convalescent host (Wotzka et al., 2017).

Even though this is just the tip of the iceberg, the mechanistic underpinnings of microbiota function are now within reach. This type of approach will advance our understanding of the basic principles that shape the microbiota community structure and drive inter-microbial interactions. We expect that the underlying principles will help to design new strategies to prevent pathogen up-growth in the gut.

Literature

Stecher, B., R. Robbiani, A. W. Walker, A. M. Westendorf, M. Barthel, M. Kremer, S. Chaffron, A. J. Macpherson, J. Buer, J. Parkhill, G. Dougan, C. von Mering, and W. D. Hardt*. (2007) Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium exploits inflammation to compete with the intestinal microbiota. PLoS Biol. 5(10):2177-89. external page[Abstract]call_made

Stecher, B.*, Chaffron, S., Käppeli, R., Hapfelmeier, S., Freedrich, S., Weber, T.C., Kirundi, J., Suar, M., McCoy, K.D., von Mering, C., Macpherson, A.J. and W. D. Hardt (2010). Like will to like: abundances of closely related species can predict susceptibility to intestinal colonization by pathogenic and commensal bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 6(1):e1000711. external page[Abstract]call_made

Stecher, B.* and W. D. Hardt*. (2010) Mechanisms controlling pathogen colonization of the gut. Curr Opin Microbiol. 14(1):82-91. external page[Abstract]call_made

Endt K., Stecher B., Chaffron S., Slack E., Tchitchek N., Benecke A., Van Maele L., Sirard J.C., Mueller A.J., Heikenwalder M., Macpherson A.J., Strugnell R., von Mering C., Hardt W. D. (2010) The microbiota mediates pathogen clearance from the gut lumen after non-typhoidal Salmonella diarrhea. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Sep 9;6(9):e1001097. external page[Abstract]call_made

Stecher, B., Maier, L. and W. D. Hardt*. (2013) 'Blooming' in the gut: how dysbiosis might contribute to pathogen evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol. (4):277-84. external page[Abstract]call_made

Maier, L., Vyas, R., Cordova, C.D., Lindsay, H., Schmidt, T.S.B., Brugiroux, S., Periaswamy, B., Bauer, R., Sturm, A., Schreiber, F., von Mering, C., Robinson, M.D., Stecher, B. and W.D. Hardt* (2013) Microbiota-Derived Hydrogen Fuels Salmonella Typhimurium Invasion of the Gut Ecosystem. Cell Host&Microbe, 14(6):641-51. external page[Abstract]call_made

Maier, L., Barthel, M., Stecher, B., Maier, R.J., Gunn, J.S. and W.D. Hardt* (2014) Salmonella Typhimurium strain ATCC14028 requires H2-hydrogenase for growth in the gut, but not at systemic sites. PLoS One, 9(10):e110187. external page[Abstract]call_made

Moor K., Diard M., Sellin M.E., Felmy B., Wotzka S.Y., Toska A., Bakkeren E., Arnoldini M., Bansept F., Co A.D., Völler T., Minola A., Fernandez-Rodriguez B., Agatic G., Barbieri S., Piccoli L., Casiraghi C., Corti D., Lanzavecchia A., Regoes R.R., Loverdo C., Stocker R., Brumley D.R., Hardt W.D., Slack E. (2017) High-avidity IgA protects the intestine by enchaining growing bacteria. Nature. Apr 27;544(7651):498-502. external page[Abstract]call_made

Diard, M., Bakkeren, E., Cornuault, J. K., Moor, Hausmann, A., Sellin, M.E., Loverdo, C., Aertsen, A., Ackermann, M., De Paepe, M., Slack, E. and Hardt, W.D. (2017) Inflammation boosts bacteriophage transfer between Salmonella spp. Science. Mar 17, Vol. 355, pp 1211–1215. external page[Abstract]call_made

Wotzka S.Y., Nguyen B.D., Hardt W.D. (2017) Salmonella Typhimurium Diarrhea Reveals Basic Principles of Enteropathogen Infection and Disease-Promoted DNA Exchange.Cell Host Microbe. 2017 Apr 12;21(4):443-454. external page[Abstract]call_made